Artificial Intelligence Helps Us Study How Birds Migrate at Night

Block title

By: Debbie LeickAvian Scientist

By: Debbie LeickAvian ScientistAvian Ecology

We seek to understand how birds use the habitats available and how that will change as we work to create more diverse plant communities. We also host researchers that document migrations of raptors and songbirds across MPG.

In this section of the research pages, you will find links to reports and updates from all the researchers involved with avian ecology, posted chronologically. The links will show you more in-depth reports on our findings. The three main projects covered here are:

Songbird Counts- A grid of sampling points covers MPG with 560 points. We visit each point 3 times a year, once in winter and twice during the songbird breeding season. We record, by ear or by sight, all the birds near that point for 10 minutes.

Songbird Banding- The University of Montana Bird Ecology Lab, UMBEL, runs several trapping stations at MPG as part of their regional songbird monitoring program. UMBEL sets up very fine nets that are nearly invisible to birds in brushy habitats. Songbirds fly into the nets and become entangled. The researchers take the birds from the nets and affix a numbered band to their leg before releasing them.

Raptor Research- The Raptor View Research Institute monitors raptor populations on MPG and counts raptors that migrate past MPG in the spring and fall. Raptor View researchers have placed transmitters on osprey and golden eagles that use the Bitterroot Valley.

Lesley Rolls helps process recordings of nocturnal flight calls.

Artificial intelligence describes how a computer program can think and learn like the human brain. We worked with the software developer, Harold Mills (human intelligence), and customized his free software, called Vesper, to process our nocturnal recordings (artificial intelligence). Harold “trained” Vesper to extract bird calls of interest, incorporating thousands of examples we previously identified. Vesper reduces years of recordings to short clips of sound that match the training samples. The software processes recordings about 150 times faster than a human, but our eyes and ears still do a better job of picking out the correct sounds. So, after the computer identifies the sounds it thinks we want, we review the results and correct any mistakes.

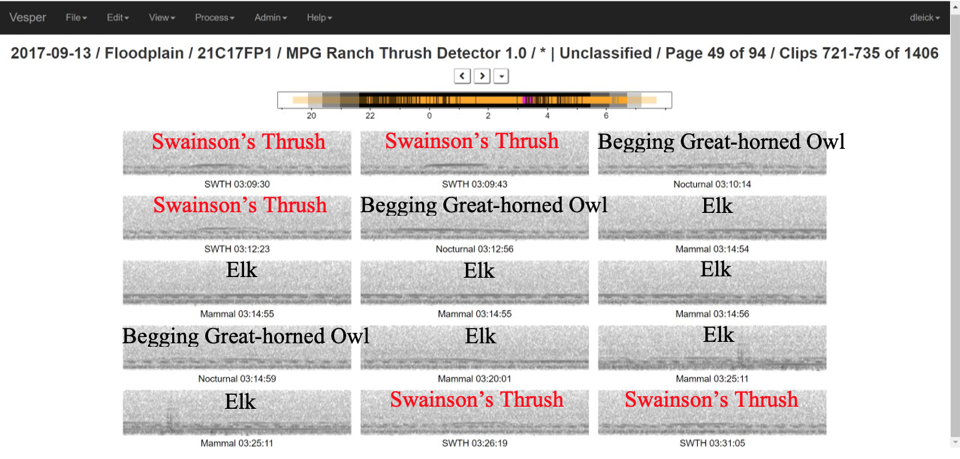

This screenshot from Vesper shows the sound clips identified as bird calls of interest. The software got some right (displayed in red), but it also included calls from elk and juvenile Great-horned Owls. These sounds were misidentified because they fall within the same frequency range and time frame as some of our migratory thrush species.

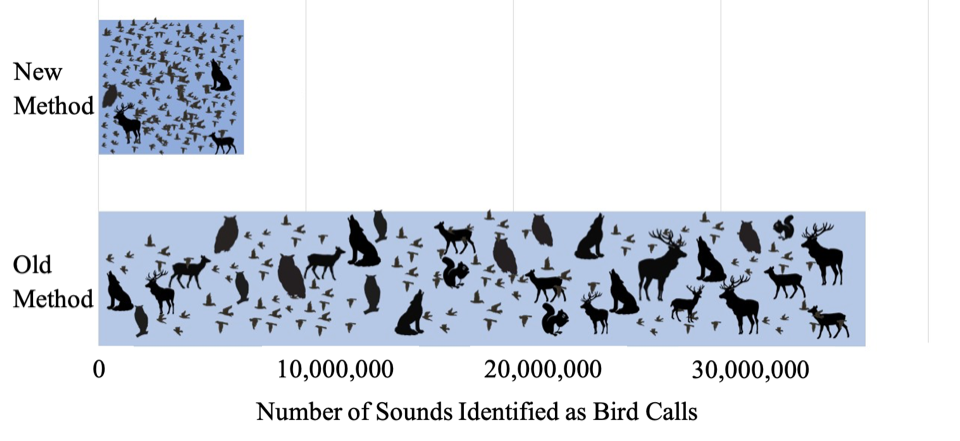

In 2019, we switched from older to newer programming. The change improved the computer’s accuracy to pick out the correct bird calls while also finding more calls of interest. The old method, developed 20 years ago, was based on recordings from the eastern US. The new one uses our recordings from western Montana to train Vesper. We ran all of our recordings using both the new and old programs and compared how each performed. The older process identified 37 million calls. The new one found many fewer, with just under 7 million.

The new method detects more flight calls and excludes non-target sounds better than the old method, cutting down the amount of time required to verify the results.

Why the big difference between the two methods? Most of the sounds detected by the old method represented calls from animals we do not want to study. Elk bugles, hungry owlets, and chirping crickets clutter our recordings and confuse the software. The new method is “smarter” and has eliminated the review of 30,000,000 sound clips, saving an estimated three years of work.

Vesper software testers from all over the United States volunteer with us to provide feedback as they process vast amounts of their data. As their participation grows, Vesper will continue to improve, helping researchers learn about how birds migrate at night.

You can find more information on Vesper here: https://vesper.readthedocs.io/en/latest/

We now have a small team of people using Vesper, who work from their customized workspaces.

About the AuthorDebbie Leick

Debbie graduated from the University of Wisconsin-Madison with a degree in pharmacy. She worked several years in traditional pharmacy and 10 years in the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industry. A passion for birds led her away from pharmacy and towards avian-related research projects and fieldwork in Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming. In 2011, she received a certificate from the University of Montana in Geographic Information Systems (GIS) Sciences and Technology, though her favorite elective class was ornithology.

At MPG Ranch, Debbie leads the avian and bat acoustic monitoring project, conducts year-round bird surveys, and performs GIS-related analyses and mapping tasks. When not behind a pair of binoculars or a computer screen, she enjoys anything outdoors especially if it involves birds or snow.

At MPG Ranch, Debbie leads the avian and bat acoustic monitoring project, conducts year-round bird surveys, and performs GIS-related analyses and mapping tasks. When not behind a pair of binoculars or a computer screen, she enjoys anything outdoors especially if it involves birds or snow.

Previous Dispatch:

Is Western Montana a Migration Corridor for Upland Sandpipers?