Do Red-breasted Nuthatch Migrate Triennially?

Block title

By: Kate StoneM.S. Avian Scientist

By: Kate StoneM.S. Avian ScientistAvian Ecology

We seek to understand how birds use the habitats available and how that will change as we work to create more diverse plant communities. We also host researchers that document migrations of raptors and songbirds across MPG.

In this section of the research pages, you will find links to reports and updates from all the researchers involved with avian ecology, posted chronologically. The links will show you more in-depth reports on our findings. The three main projects covered here are:

Songbird Counts- A grid of sampling points covers MPG with 560 points. We visit each point 3 times a year, once in winter and twice during the songbird breeding season. We record, by ear or by sight, all the birds near that point for 10 minutes.

Songbird Banding- The University of Montana Bird Ecology Lab, UMBEL, runs several trapping stations at MPG as part of their regional songbird monitoring program. UMBEL sets up very fine nets that are nearly invisible to birds in brushy habitats. Songbirds fly into the nets and become entangled. The researchers take the birds from the nets and affix a numbered band to their leg before releasing them.

Raptor Research- The Raptor View Research Institute monitors raptor populations on MPG and counts raptors that migrate past MPG in the spring and fall. Raptor View researchers have placed transmitters on osprey and golden eagles that use the Bitterroot Valley.

Eric Rasmussen captured this picture of an inquisitive Red-breasted Nuthatch overwintering in the Bitterroot Valley.

As the bird crew dives deep into our archive of fall migration acoustic data, we sometimes find surprises beyond the typical thrush, sparrow, and warbler nocturnal flight calls. As I was proofing fall 2020 data from the MPG Ranch floodplain, the quiet, beguiling, and familiar "yank" of a Red-breasted Nuthatch broke the otherwise steady stream of Swainson's Thrush flight calls. I paused and saw a spectrogram that looked vaguely like a layer cake, not a hockey stick. I checked the time and saw "0:35 am", well outside of the timeframe, we would expect activity from a resident, diurnal bird.

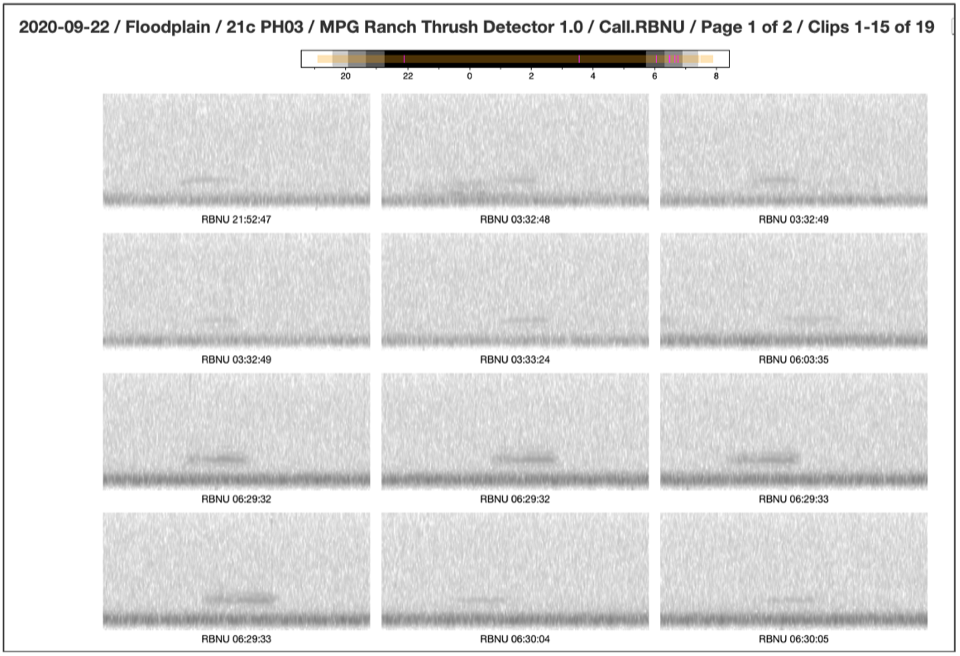

We use the custom, open-source software Vesper to manage our acoustic data. The "thrush" detector we use isolates sound clips of duration and frequency similar to the nocturnal flight call of a Swainson's Thrush (left). The software extracts all calls with similar characteristics, allowing detections like the Red-breasted Nuthatch (right).

Though not a typical migrant like many songbirds, Red-breasted Nuthatch populations exhibit periodic irruptions, where groups move in flocks through the fall and winter. Last October, a social media post by our friends at the Intermountain Bird Observatory near Boise alerted me to watch out for large numbers of nuthatches. And indeed, as I birded this fall and even into the winter, I counted high numbers, particularly in Ponderosa Pine forests. I even saw flocks on the ground, not the usual place to observe this lover of tree trunks and side branches. They joined chickadees, Clark's Nutcrackers, and Red-winged Blackbirds, all extracting seeds from pinecones. But despite seeing so many, it never crossed my mind that we might pick them up on our acoustic monitors.

After my initial acoustic encounter, I noted a handful of nuthatches passing through on 12 of the 14 September nights I looked at, most occurring during the second half of the month.

This screenshot of our Vesper software interface shows the spectrograms and timestamps for Red-breasted Nuthatches during one September night. When we scroll through these spectrograms for proofing, we also hear the associated audio.

These detections match up nicely with the high numbers captured by biologists from the University of Montana Bird Ecology Lab (UMBEL) in 2020, most from mid-to late-September.

Fall banding data from UMBEL on the MPG Ranch floodplain suggests pulses of Red-breasted Nuthatches every three years, including 2020.

We checked with other folks monitoring migration acoustically, and it turns out other sites observed similar patterns, including stations at Cape May, New Jersey, central New York, and Novia Scotia.

We haven't yet processed all of our 2020 data but look forward to seeing if we detected nuthatch migration at other acoustic monitors. In the meantime, when a "yank yank" call stops me in my tracks on a winter bird walk, I wonder if any of my nuthatch neighbors arrived here from distant places after adding surprise to our fall nocturnal soundscape.

About the AuthorKate Stone

Kate graduated from Middlebury College with a B.A. in Environmental Studies and Conservation Biology in 2000. She pursued a M.S. in Forestry at the University of Montana where her thesis focused on the habitat associations of snowshoe hares on U.S. National Forest land in Western Montana. After completing her M.S. degree in 2003, Kate alternated between various field biology jobs in the summer and writing for the U.S. Forest Service in the winter. Her fieldwork included projects on small mammal response to weed invasions, the response of bird communities to bark beetle outbreaks and targeted surveys for species of concern like the black-backed woodpecker and the Northern goshawk. Writing topics ranged from the ecology and management of western larch to the impacts of fuels reduction on riparian areas.

Kate coordinates bird-related research at the MPG Ranch. She is involved in both original research and facilitating the use of the Ranch as a study site for outside researchers. Additionally, Kate is the field trip coordinator and website manager for the Bitterroot Audubon Society. She also enjoys gardening and biking in her spare time.

Kate coordinates bird-related research at the MPG Ranch. She is involved in both original research and facilitating the use of the Ranch as a study site for outside researchers. Additionally, Kate is the field trip coordinator and website manager for the Bitterroot Audubon Society. She also enjoys gardening and biking in her spare time.