Altering Western White Pine Microbiomes For Disease Resistance

Block title

By: Lorinda BullingtonEcologist and Bioinformatics Analyst

By: Lorinda BullingtonEcologist and Bioinformatics AnalystSoils Plants and Invasion

Plants live in tight associations with microbes who colonize their roots and leaves and surrounding soil. Some microbes are harmful and cause disease while others are beneficial and aid in plant nutrient uptake, decomposition of organic materials, protection against pathogens, tolerance against drought and other stressors. Plants can influence microbial communities and vice versa with consequences for the growth of individual plants, the composition of plant communities, and entire ecosystems. In our work, we focus on three main aspects of plant-microbe interactions; 1) how they may aid or hinder plant invasions, 2) how their function changes across environmental gradients, and 3) how they may both cause and prevent disease in plants.On MPG Ranch, three highly invasive weeds of contrasting lie history strategies (cheatgrass, knapweed and leafy spurge) co-occur with remnants of native plant vegetation. Using both observational and experimental approaches, we seek to understand how these weeds alter microbial communities and how this influence invasive success, ecosystem properties and restoration. We also collaborate with researchers from across the world to learn if plant-microbe interactions differ between native and invasive ranges and how this correlates with evolutionary shifts in plant genomes and biogeographical distribution of plant associated microbes.

Outcomes of plant-soil microbe interactions depend on the particular plant and fungal species and surrounding environmental conditions. To explore this context-dependency, we use high-throughput sequencing and stable and radioactive isotopes in surveys and experiments to determine if the proportion of fungal guilds (mutualistic mycorrhizal fungi and potential pathogens) change with water and nutrient availability and how these changes relate to plant growth. Because most research occurs in single locations, the generality of findings across locations that differ in environmental conditions is often unknown. To address this, MPG Ranch is part of two global research collaborations, Nutrient Network (https://nutnet.org) and DroughtNet (www.drought-net.org). In these experiments, all researchers apply nutrients, remove herbivores, expose plants to drought, and record responses in both plant and microbial communities using the same protocols, which allow for direct comparisons across sites.

The invasive fungal pathogen, Cronartium ribicola, causes the disease commonly known as blister rust in all nine white pine species native to the United States. As one of the only labs in the world to grow C. ribicola in culture, we perform tests of pathogen metabolism when exposed to compounds produced by other fungi found in white pine needles. Greenhouse experiments inoculating trees with these fungi, as well as beneficial ectomycorrhizal fungi, explore how we can improve tree growth and disease resistance. We also use isotopes and controlled field experiments to determine how blue-stain fungi carried by bark beetles can influence wood decomposition in forest ecosystems. As warming climates increase the frequency of bark beetle outbreaks worldwide, this research will help to better estimate future forest carbon storage and release.

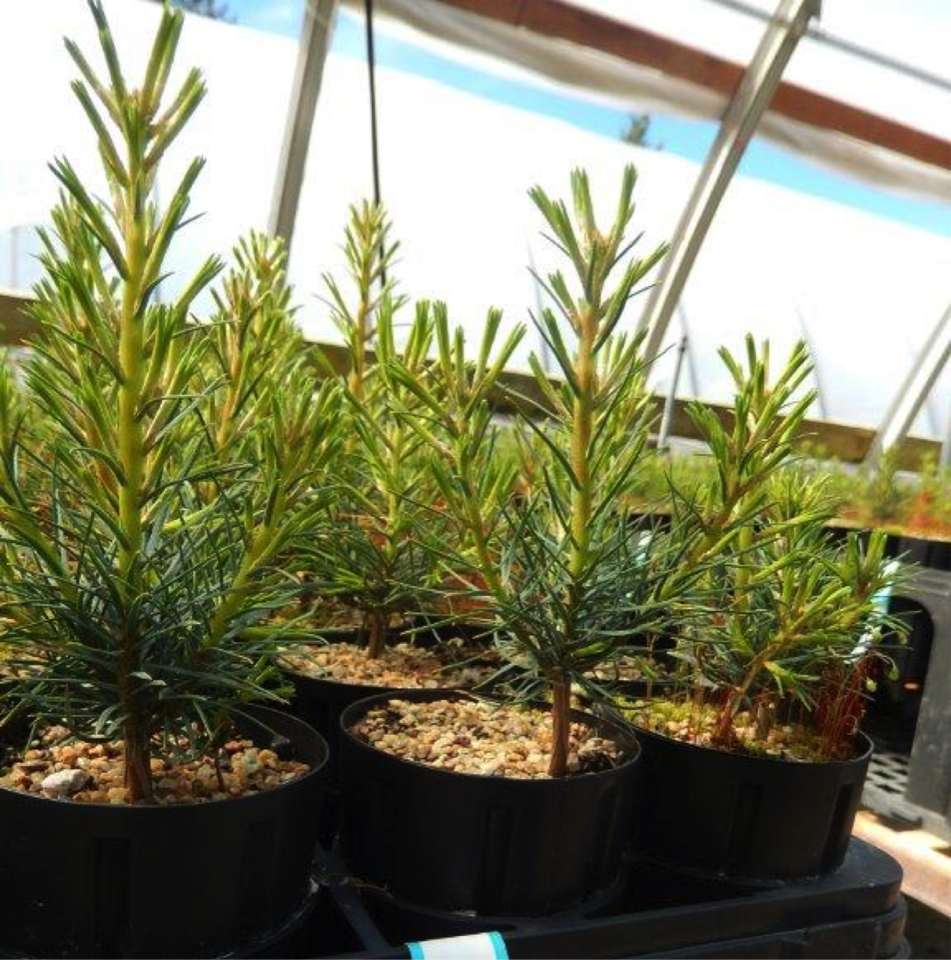

In May 2019, we sprayed hundreds of western white pine seedlings with an experimental fungal microbiome. This effort was part of a greenhouse experiment to determine how fungi can influence disease caused by the blister rust pathogen, Cronartium ribicola.

On September 19th, 2019, seedlings were exposed to C. ribicola spores in the fog chamber (above), at the Dorena Genetic Resource Center in Eugene, OR. Hundreds of Ribes leaves naturally infected with the blister rust pathogen (below), were used to spread disease to the seedlings.

Leaves were placed spore-side down on racks above white pine seedlings (above). Artificial fog induces the release of spores to increase pathogen infection. A subset of seedlings was destructively sampled to determine the success of our May inoculations. We will have results of that analysis later this fall.

About the AuthorLorinda Bullington

Lorinda is currently a Ph. D. student at the University of Montana, studying systems ecology. She also has a master’s degree in molecular ecology, a B.S. degree in microbiology, and a certificate in bioinformatics. Her research investigates how plant-associated microbial communities (plant microbiomes), influence plant growth, defensive chemistry, disease, and nutrient cycling. Lorinda comes from three generations of small-scale Montana loggers and is particularly interested in microbial communities in forest ecosystems. She has published research on fungi associated with native white pines and their influence on tree defensive chemistry and the invasive pathogen Cronartium ribicola, which causes white pine blister rust disease. She also works in collaboration with others at UM studying the influence of bark beetle infestations on fungal decomposer communities, with implications on nutrient turnover and carbon sequestration in forests.

In addition to her own research, Lorinda often assists other researchers in bioinformatics analyses and is currently working on multiple diet-barcoding studies to better understand food web ecology and dynamics across the landscape. For a complete list of Lorinda’s publications, click here.

Lorinda is currently a Ph. D. student at the University of Montana, studying systems ecology. She also has a master’s degree in molecular ecology, a B.S. degree in microbiology, and a certificate in bioinformatics. Her research investigates how plant-associated microbial communities (plant microbiomes), influence plant growth, defensive chemistry, disease, and nutrient cycling. Lorinda comes from three generations of small-scale Montana loggers and is particularly interested in microbial communities in forest ecosystems. She has published research on fungi associated with native white pines and their influence on tree defensive chemistry and the invasive pathogen Cronartium ribicola, which causes white pine blister rust disease. She also works in collaboration with others at UM studying the influence of bark beetle infestations on fungal decomposer communities, with implications on nutrient turnover and carbon sequestration in forests.

In addition to her own research, Lorinda often assists other researchers in bioinformatics analyses and is currently working on multiple diet-barcoding studies to better understand food web ecology and dynamics across the landscape. For a complete list of Lorinda’s publications, click here.