Dry-Land Tracking

Block title

David Moskowitz, a professional tracker, visited MPG to teach a three day tracking workshop for ranch staff and contributors who conduct carnivore surveys. Dave began by comparing his methodology to a detective’s interpretation of a crime scene. Because all tracks and sign provide ‘evidence’ of past animal activity, we can make observations about the sign, use context clues in the surrounding environment, and use a deductive process to assemble a reasonable narrative about the event.

The first day focused on non-track sign and foot morphology. Non-track sign includes rubs, scrapes, incisor (teeth) and claw marks on trees, kill sites, scat, etc. Above, Beau mimics the paw position of the bear that climbed the aspen tree.

Another aspen tree, shown above, wore various rubs and scrapes. The group first assumed that a bear caused these injuries to the tree, but to the our surprise, elk had caused the damage. The marks consisted of antler rubs, incisor marks, scent marking, and feeding on the tree’s cambium. Cracks associated with tree growth had also intertwined with the marks left by elk. Dave reached this conclusion by considering the shape of a woodworking tool that could create the marks. For example, incisor scraping would resemble the mark left by a scoop chisel, and a bear claw scratch might resemble an awl. Using this approach made it easier to rule out bear activity because they do not possess the right ‘tools for the job’.

Day one closed with an indoor lesson on foot morphology of various species. We learned how structural features of animals’ feet leave distinctive imprints in the field.

The second day focused on track identification. We tested our new confidence in foot structure analysis in the wet sand of the Bitterroot floodplain.

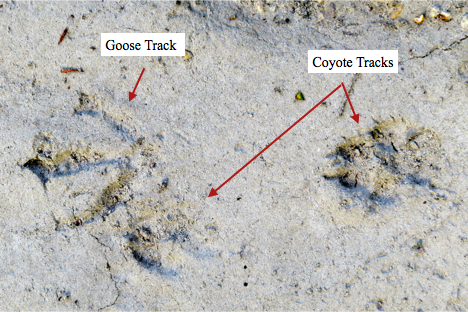

We found numerous coyote tracks in the sandy backchannels, shown above along with a Canada goose track.

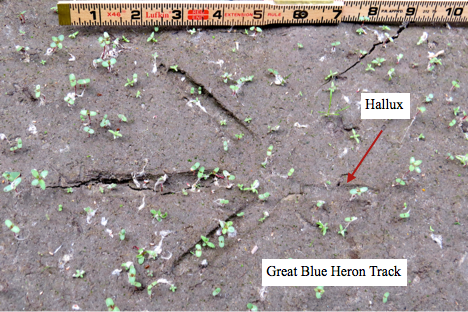

We also saw great blue heron and sandhill crane tracks, shown above. In the heron track, the hallux (rear toe) registered clearly, but it did not register in the crane track. The hallux resembles a rear-facing toe that allows birds to grasp a perch (or prey). The great blue heron’s large and distinctive hallux does not align with the center, forward-facing toe, making them easy to identify from tracks.

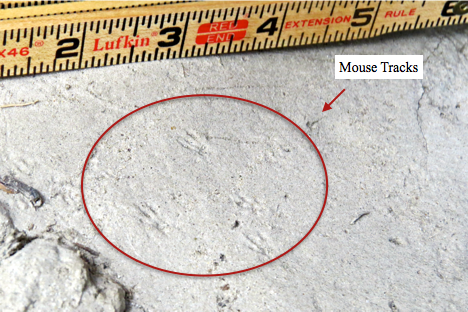

The class moved on to look at travel corridors and habitat. In the image above, the larger sandy channel behind the group provides an excellent travel corridor for coyotes and other large predators. Smaller carnivores such as weasels might hunt around and under the log. In the log we found tracks left by a western harvest mouse (below).

Our third and final day focused on following animals over terrain. The day started in Davis Creek in the northeast corner of the property. Heavy wildlife use in this area leaves copious sign. We immediately found evidence of cambium feeding and elk incisor marks (above).

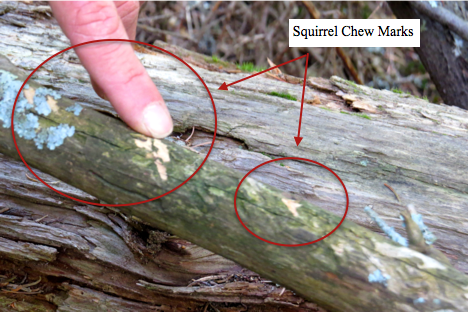

One of the more unusual discoveries of the day was also the smallest. In the photo above, Dave points to territorial marks left by squirrels. The red circles surround the most recent and obvious chewing, but further inspection revealed the marking behavior of past generations of squirrels. Many observers, keen to follow only large game animals, might miss this small detail.

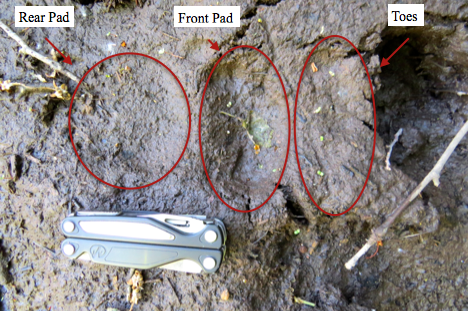

We returned to our hike and found what looked like random depressions in mud (above). Upon further inspection, we realized that a medium-sized black bear had left this track. The clear image of a black bear track in snow is included for comparison below.

We also discovered numerous mountain lion scrapes. Lions scrape to mark their territory and communicate with each other. They prefer to scrape in soft duff beneath trees. Lions scrape away needles with their hind paws and then scent mark the resulting pile. In recent and well-defined scrapes, the paw marks appear as two ‘ski tracks’ with a pile at one end. The road bed we traveled had one scrape every 50 yards or so, suggesting that lions frequent this area.

We closed the day by trailing elk. Once we found the fresh tracks of a browsing herd, we followed them through the brush and mountainous terrain. This task proved difficult. Identifying the tracks of meandering elk from their braided trails required time and patience. Despite the difficulty presented by dry conditions, we persevered with the use of keen eyes, an understanding of elk behavior, and the application of a deductive process to interpret what little sign occurred.