Gored

Block title

By: Craig JourdonnaisBig Game Researcher

By: Craig JourdonnaisBig Game ResearcherMammals

We seek to understand the distribution and abundance of mammals. Several monitoring projects are underway.

Elk- Elk numbers fluctuate through the year with herds of several hundred animals moving onto the ranch in the fall and winter. Fewer elk stay around to raise their calves in the spring and summer. We track herd size, the habitat they use for feeding, and the amount of biomass available to them for forage. We are curious about how elk habits will change in response to changes in vegetation communities as restoration activities proceed.

Bears- The lower elevation draws and drainages at MPG were de-vegetated by herbicide applications and sheep and cattle browsing. As of the summer 2012, we have planted more than 30,000 trees and shrubs in these drainages. The plantings will provide cover for animals using the draw bottoms as travel corridors between the upland forests and the floodplain forests. Many of the shrubs we have planted, such as hawthorns, choke cherries, and serviceberry, will provide food for bears. Our bear monitoring efforts seek to document how many bears we have now and where they travel.

Click here for a link to a list of mammals we have seen and photos.

Click here for links to our best mammal footage.

We would like to do more small mammal research. Please contact us with ideas for collaboration. (Click here to contact us.)

Elk Rut is Serious Stuff

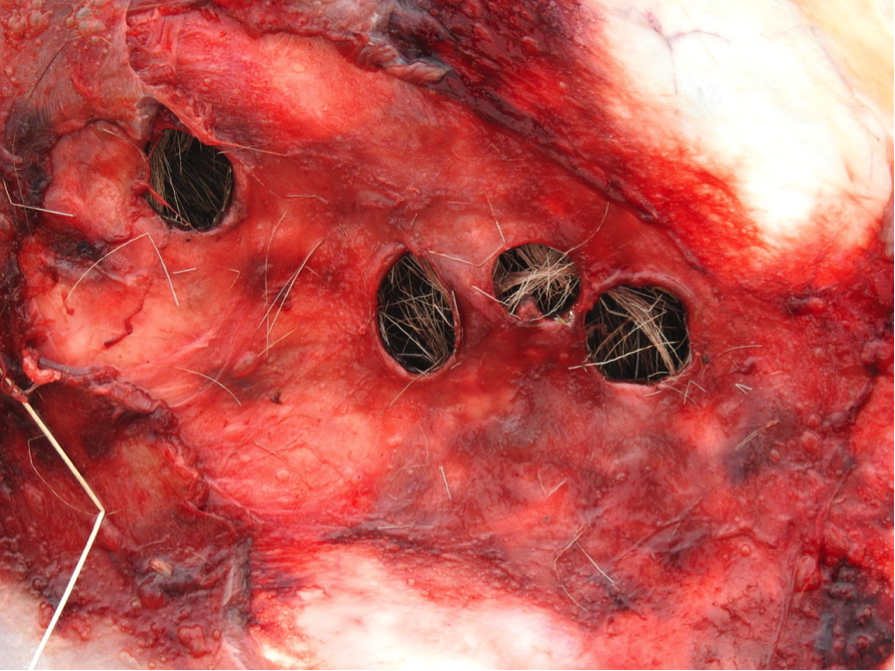

*Warning* photos in this dispatch are explicit, viewer be advised.

There’s an old saying that ‘if you mess with the bull you get the horns’. That literally happens in a bull elk’s world.

This bull lost his title match and his life in a battle with another bull this fall on MPG Ranch. His battered body and the massive chunks of turf torn up around him suggest this bout went into the late rounds.

Fights between bulls of equal antler and body mass are common during the breeding season. Savagery is on full display during these bouts. Males clash antlers, twist their heads, and surge forward using their body mass and agility to force their opponent backward or off balance. Each combatant tries to overpower the other.

Bulls often settle these encounters in a few minutes. Extended fights between well-matched opponents may last well beyond an hour, leaving both males exhausted.

These violent episodes can result in puncture marks, scars, broken teeth and antlers, and even injured eyes and legs.

The objective is securing dominance over a rival. There’s no ‘Fairness Doctrine’ or standing 8-count between opponents. If they have a chance to kill their rival, there’s no hesitation.

Fatalities happen.

Occasionally, antlers become hopelessly locked. Death to either combatant may take days.

Also, fatalities occur when the weaker opponent initiates a retreat but stumbles, gets turned onto his back, and the opponent twists the weaker bull’s neck and antlers. The stronger bull could also catch his opponent in an awkward position (usually broadside), knocking the opponent to his side.

The dominant bull’s motive becomes shockingly clear as he seizes the moment with eye-opening violence. He uses his body weight (over 1,000 pounds for mature bull elk) to plunge his tines into his opponent’s prone body. Often, fatal injuries result.

Dr. Val Geist, an expert in deer behavior, observed that hides from adult mule deer bucks exhibited extensive scars, some having over 100. Geist suggested many of these come from fighting.

This old warrior serves as evidence to the violence in a bull elk’s world. His hide had at least 6 puncture wounds, and a view of the inside of his rib cage exposed several broken ribs and extensive muscle damage.

About the AuthorCraig Jourdonnais

Craig graduated with a B.S. in wildlife management in 1982 and completed his M.S. degree in Range Management in 1985 from the University of Montana School of Forestry. Craig worked seasonal wildlife tech positions with U.S. Forest Service, Bitterroot National Forest and Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks during his college career. Craig completed his Master’s research using prescribed fire and cattle grazing on a rough fescue winter range to improve elk forage conditions on the Sun River Wildlife Management Area. Results from this research are published in the Wildlife Society Bulletin.

Craig spent the next 33 years working for Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks. He spent one year on the East Front Grizzly Project, 3 years as a state game warden, 15 years as a statewide wildlife video production specialist and his remaining tenure as the area wildlife biologist in the Gallatin, Madison and Bitterroot Valleys.

Craig works as a youth hunt coordinator and big game researcher for MPG Ranch. Craig spends his time away from MPG Ranch with his family hunting, fishing, floating and hiking. He is a competitive swimmer and coaches U.S. Masters swimming, teaches big game management for One Montana’s Montana Hunter Advancement Program, and serves as Big Game Committee Chairman for the Ravalli County Fish and Wildlife Association.

Craig spent the next 33 years working for Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks. He spent one year on the East Front Grizzly Project, 3 years as a state game warden, 15 years as a statewide wildlife video production specialist and his remaining tenure as the area wildlife biologist in the Gallatin, Madison and Bitterroot Valleys.

Craig works as a youth hunt coordinator and big game researcher for MPG Ranch. Craig spends his time away from MPG Ranch with his family hunting, fishing, floating and hiking. He is a competitive swimmer and coaches U.S. Masters swimming, teaches big game management for One Montana’s Montana Hunter Advancement Program, and serves as Big Game Committee Chairman for the Ravalli County Fish and Wildlife Association.