Scavenger Hunt

November 8th, 2018

Block title

By: Mike McTeeResearcher

By: Mike McTeeResearcherand Kate Stone

Research Methods:

Scavengers love eating wobbly organs and the flesh that hunters leave in the woods. In fact, many scavengers rely on such carrion. That’s why Kate Stone and I posted a flier on Facebook last month that asked hunters for a favor. We wanted them to put game cameras on the gut piles and carcasses they left in the field. This would help us learn about the role that hunters play in the ecology of scavengers.

Three hours later, my phone buzzed with a text. “Hey man, I’ll carry a camera to put up,” my neighbor wrote. “I’ve always wanted to do that.”

As our project built momentum, we realized that much of the local hunting community shared my neighbor’s enthusiasm. It’s easy to be excited when your gut pile could feed golden eagles that breed in Alaska and overwinter in Montana, or maybe a grizzly bear that strayed from its core range to eat worms on a golf course.

But before we began distributing cameras to the public, we put cameras on gut piles at MPG Ranch. The cameras consistently photographed magpies, which may not thrill readers, but the magpies may have helped lure in other more charismatic scavengers, like this golden eagle.

A pair of golden eagles fed on this elk carcass for at least two days. Photos from the second day revealed a metallic band on this eagle’s right leg.

Numbers that identify the bird are etched into the band. Can you see the numbers? Neither can we. That is why our colleagues at Raptor View Research Institute put vinyl wing tags on some of the eagles they catch. The tags are blue and highly visible, so when an eagle feeds on a carcass monitored by a camera, we should be able to identify it and learn about its history. Some eagles are equipped with GPS transmitters and you can see their movements on our Raptor Tracker. Any hunter who photographs one of these tagged birds with a game camera earns a prize!

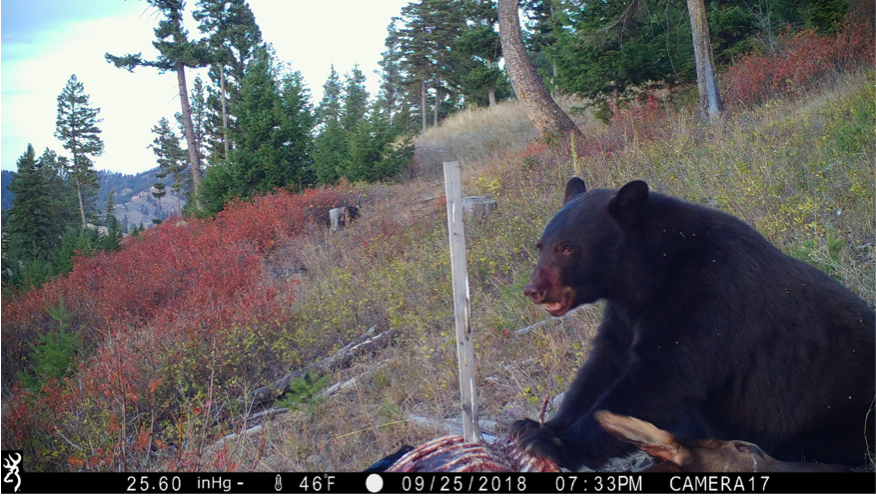

Between visits by the eagles, a black bear covered its face in organ juice and sucked down the remains.

Miles away and a month earlier, an eagle arrived before a black bear too. Here, a juvenile bald eagle visited sagebrush country for an evening snack.

Before the black bear arrived, two coyotes investigated.

Then, of course, the bear…

In the morning, magpies searched for scraps. Each gut pile that we monitored at MPG Ranch disappeared within a week.

One of the first cameras deployed by a public hunter caught a coyote peering towards the camera. Afterwards, the coyote and its buddies dragged the carcass away towards privacy.

One hunter legally dumped his butchering scraps onto a brush pile on his property. A skunk searched through the remains the first night.

While a pair of raccoons clawed their way into the scraps the second night.

But before the camera captured the skunk and raccoons, it photographed one of the least appreciated scavengers of all: The domestic chicken!

If you would like to see or share what eats the gut piles and carcasses you leave in the field, feel free to contact us at [email protected] .

About the AuthorMike McTee

Mike McTee is a researcher at MPG Ranch and the author of Wilted Wings: A Hunter’s Fight for Eagles.

Mike shot his first weapon before he could recite the alphabet. Now, understanding weapons is part of his job. His career took this trajectory after Mike gained a B.S. in Environmental Chemistry. Curious about potential pollution at a historic shooting range at MPG Ranch, he earned an M.S. in Geosciences studying the site. Strangely, the sulfur inside the trap and skeet targets posed the main threat, not the lead in the shotgun pellets. Regardless, lead contamination soon grabbed Mike’s focus. Each winter at MPG Ranch, biologists caught eagles that had lead coursing through their veins. Lead can cripple eagles flightless and even kill them. Mike soon initiated studies on scavenger ecology and began investigating the wound ballistics of rifle bullets, the suspected source of lead.

Mike often connects with the public through his writings and speaking engagements, whether it be to a local group of hunters, or a gymnasium full of middle schoolers. He frequently writes about the outdoors, with work appearing in Sports Afield, The Drake, and Bugle. When he escapes the office, Mike explores wild landscapes with his family, always scanning the horizon for wildlife.

Sign up for Montana’s Nonlead Newsletter (see past editions).

Mike McTee is a researcher at MPG Ranch and the author of Wilted Wings: A Hunter’s Fight for Eagles.

Mike shot his first weapon before he could recite the alphabet. Now, understanding weapons is part of his job. His career took this trajectory after Mike gained a B.S. in Environmental Chemistry. Curious about potential pollution at a historic shooting range at MPG Ranch, he earned an M.S. in Geosciences studying the site. Strangely, the sulfur inside the trap and skeet targets posed the main threat, not the lead in the shotgun pellets. Regardless, lead contamination soon grabbed Mike’s focus. Each winter at MPG Ranch, biologists caught eagles that had lead coursing through their veins. Lead can cripple eagles flightless and even kill them. Mike soon initiated studies on scavenger ecology and began investigating the wound ballistics of rifle bullets, the suspected source of lead.

Mike often connects with the public through his writings and speaking engagements, whether it be to a local group of hunters, or a gymnasium full of middle schoolers. He frequently writes about the outdoors, with work appearing in Sports Afield, The Drake, and Bugle. When he escapes the office, Mike explores wild landscapes with his family, always scanning the horizon for wildlife.

Sign up for Montana’s Nonlead Newsletter (see past editions).

Mike shot his first weapon before he could recite the alphabet. Now, understanding weapons is part of his job. His career took this trajectory after Mike gained a B.S. in Environmental Chemistry. Curious about potential pollution at a historic shooting range at MPG Ranch, he earned an M.S. in Geosciences studying the site. Strangely, the sulfur inside the trap and skeet targets posed the main threat, not the lead in the shotgun pellets. Regardless, lead contamination soon grabbed Mike’s focus. Each winter at MPG Ranch, biologists caught eagles that had lead coursing through their veins. Lead can cripple eagles flightless and even kill them. Mike soon initiated studies on scavenger ecology and began investigating the wound ballistics of rifle bullets, the suspected source of lead.

Mike often connects with the public through his writings and speaking engagements, whether it be to a local group of hunters, or a gymnasium full of middle schoolers. He frequently writes about the outdoors, with work appearing in Sports Afield, The Drake, and Bugle. When he escapes the office, Mike explores wild landscapes with his family, always scanning the horizon for wildlife.

Sign up for Montana’s Nonlead Newsletter (see past editions).

Previous Dispatch:

Next Dispatch:

Other Dispatches

Related Dispatches

Related Research

Probing the lighting sensitivity of image encoders with repeat drone imagery: A case study of plant height estimation

November 11th, 2025

By: Kyle Doherty

2024 publications by the MPG plant-soil feedback group

January 3rd, 2025