Top Model: Elk Edition

Block title

By: Mike McTeeResearcher

By: Mike McTeeResearcherMammals

We seek to understand the distribution and abundance of mammals. Several monitoring projects are underway.

Elk- Elk numbers fluctuate through the year with herds of several hundred animals moving onto the ranch in the fall and winter. Fewer elk stay around to raise their calves in the spring and summer. We track herd size, the habitat they use for feeding, and the amount of biomass available to them for forage. We are curious about how elk habits will change in response to changes in vegetation communities as restoration activities proceed.

Bears- The lower elevation draws and drainages at MPG were de-vegetated by herbicide applications and sheep and cattle browsing. As of the summer 2012, we have planted more than 30,000 trees and shrubs in these drainages. The plantings will provide cover for animals using the draw bottoms as travel corridors between the upland forests and the floodplain forests. Many of the shrubs we have planted, such as hawthorns, choke cherries, and serviceberry, will provide food for bears. Our bear monitoring efforts seek to document how many bears we have now and where they travel.

Click here for a link to a list of mammals we have seen and photos.

Click here for links to our best mammal footage.

We would like to do more small mammal research. Please contact us with ideas for collaboration. (Click here to contact us.)

Around here in Missoula, Montana, big bulls seem scarce. This is ironic because the world headquarters of RMEF is located here (Boone and Crockett is too). So, we wondered: What are the chances that a local bull could live long enough to contend for the cover of Bugle? We used data collected 20 minutes south of us to find out.

An aerial survey of the Northern Sapphire Hunting District (HD 204) tallied 1056 elk in the spring of 2016, let’s take a closer look at what they saw.

For every 20 cows and calves, there was one brow-tined bull. This lopsided cow:bull ratio suggests a high mortality rate for bulls–especially when we consider that bull calves tend to be as common as cow calves.

The question remains: Could any of these bulls be big enough for the cover of Bugle magazine? We can exclude yearling bulls, leaving us 47 brow-tined bulls. There were probably bulls that the survey missed, but hey, we’re doing our best.

These 47 bulls could theoretically be anywhere from 2 ½ to 12+ years old, and because antlers often get bigger every year, we need to know the age structure of these bulls. For example, a bull’s rack often reaches 6x6 only after its third year. Plus, bulls usually aren’t considered really big until they reach 6 ½. Rack size also depends on genetics and other factors, but overall, it works something like this:

So, here’s the real question: How many of the 47 brow-tined bulls were 6 ½ or older? Let’s use real mortality data to get an idea.

Biologists put GPS collars on 20 bulls in the Northern Sapphires in 2014. When a collar transmitted a “dead” signal, biologists located the elk and determined the cause of death. But sometimes, biologists couldn’t figure out the date and/or cause of death. For instance, on two occasions they found collars laying on the ground because had been cut off the elk. Most likely, someone killed the animal and left the collar. Nevertheless, biologists didn’t include this data or any data from a collar that malfunctioned, which led to the exclusion of seven bulls from the mortality study.

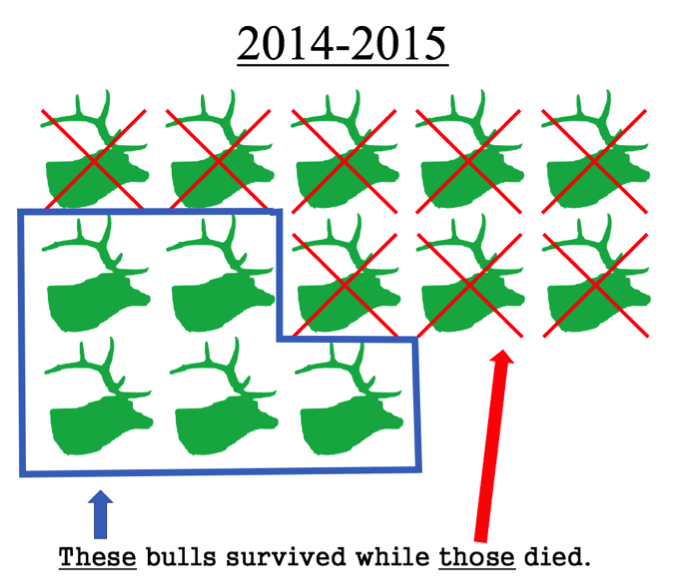

This left 13 collared bulls for consideration. Here is what happened during the study:

Biologists equipped another 8-bull elk with collars in 2015. When combined with the five collared bulls that survived from the previous year, minus bulls that had to be excluded due to reasons we previously discussed, there were 11 collared bulls heading into the following year.

54% of the bulls shown above were killed. Were predators to blame? If you said yes, good answer, but no. It’s us. All mortalities were associated with hunters. With a six-week archery season followed by a five-week rifle season, hunters had ample opportunity to fill their over the counter tag. Here is a breakdown of how the bulls were killed:

54% killed by rifle

23% wounded by rifle and lost

15% killed by archery

8% wounded by archery and lost

The results may underestimate the true overall mortality because:

-

Many bulls frequented private property that only allowed the harvest of cows.

-

Some hunters may have passed up shots on bulls that had collars.

-

The data do not include the elk whose collars were cut, even though the animals were likely killed by hunters or poachers.

Biologists calculated the annual survival rate for bulls in this study to be somewhere between 26% and 64% per year. Let’s look at the rough probability of a 2 ½ year old bull surviving four seasons to be 6 ½ years old using these survival rates.

26% x 26% x 26% x 26% = 0.05% (worst case)

64% x 64% x 64% x 64% = 17% (best case)

The chance of a bull reaching 6 ½ years old and a having shot at that Bugle cover range from 1/2000 to about 1/6.

Let’s be more conservative and say that the annual survival rate equaled 50% and we apply that rate for bulls at least 2 ½ years old and into the future. That would yield a skewed age structure like this:

This conservative survival rate doesn’t give much opportunity for elk to see the Big Old Bulls zone–although it’s possible that year-to-year variation in recruitment could lead to a greater or lesser prevalence of certain age classes.

Mortality rates can also vary from year to year and may differ depending on age class. But overall, this age structure is a reality in many hunting districts that allow unlimited over the counter tags and long hunting seasons.

What can we conclude? It is unlikely that the hunting district in the Northern Sapphires holds many bulls big enough for the cover of Bugle magazine, however, this sometimes happens:

Photo credit: Kaine Zetterberg

A rifle hunter killed this bull on public land in 2015, prior to the aerial survey. Not only did the elk live within the study area, it was part of the mortality study–notice the ear tag and collar.

This bull defied the odds by living an estimated 10 years and could clearly be a contender for the cover of Bugle magazine. This made us wonder if other bulls are defying the odds. If so, how many are left?

What about bulls in your hunting district–how old are they?

If you liked this post, please let us know on Facebook.

References

Montana, Fish, Wildlife & Parks. North Sapphire Elk Research Project. (2017)

About the AuthorMike McTee

Mike McTee is a researcher at MPG Ranch and the author of Wilted Wings: A Hunter’s Fight for Eagles.

Mike shot his first weapon before he could recite the alphabet. Now, understanding weapons is part of his job. His career took this trajectory after Mike gained a B.S. in Environmental Chemistry. Curious about potential pollution at a historic shooting range at MPG Ranch, he earned an M.S. in Geosciences studying the site. Strangely, the sulfur inside the trap and skeet targets posed the main threat, not the lead in the shotgun pellets. Regardless, lead contamination soon grabbed Mike’s focus. Each winter at MPG Ranch, biologists caught eagles that had lead coursing through their veins. Lead can cripple eagles flightless and even kill them. Mike soon initiated studies on scavenger ecology and began investigating the wound ballistics of rifle bullets, the suspected source of lead.

Mike often connects with the public through his writings and speaking engagements, whether it be to a local group of hunters, or a gymnasium full of middle schoolers. He frequently writes about the outdoors, with work appearing in Sports Afield, The Drake, and Bugle. When he escapes the office, Mike explores wild landscapes with his family, always scanning the horizon for wildlife.

Sign up for Montana’s Nonlead Newsletter (see past editions).

Mike shot his first weapon before he could recite the alphabet. Now, understanding weapons is part of his job. His career took this trajectory after Mike gained a B.S. in Environmental Chemistry. Curious about potential pollution at a historic shooting range at MPG Ranch, he earned an M.S. in Geosciences studying the site. Strangely, the sulfur inside the trap and skeet targets posed the main threat, not the lead in the shotgun pellets. Regardless, lead contamination soon grabbed Mike’s focus. Each winter at MPG Ranch, biologists caught eagles that had lead coursing through their veins. Lead can cripple eagles flightless and even kill them. Mike soon initiated studies on scavenger ecology and began investigating the wound ballistics of rifle bullets, the suspected source of lead.

Mike often connects with the public through his writings and speaking engagements, whether it be to a local group of hunters, or a gymnasium full of middle schoolers. He frequently writes about the outdoors, with work appearing in Sports Afield, The Drake, and Bugle. When he escapes the office, Mike explores wild landscapes with his family, always scanning the horizon for wildlife.

Sign up for Montana’s Nonlead Newsletter (see past editions).